Accessibility in the Library

Every school librarian’s job is different. We create welcoming environments, foster a love of reading, and promote literacies of all kinds, but we also serve students of different ages, socioeconomic backgrounds, languages, races and cultures, sexual orientations and gender identities, religions, abilities, interests, and more. We use the tools we have and the relationships we build to serve the kids in front of us.

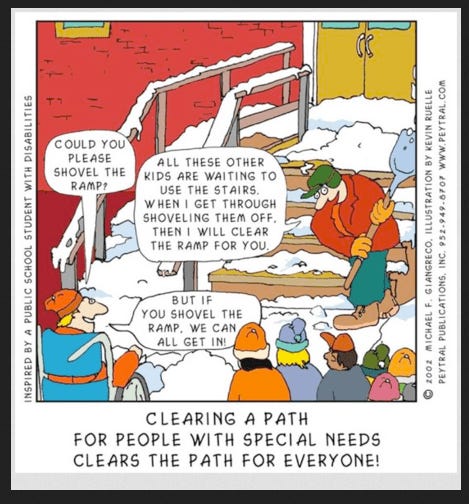

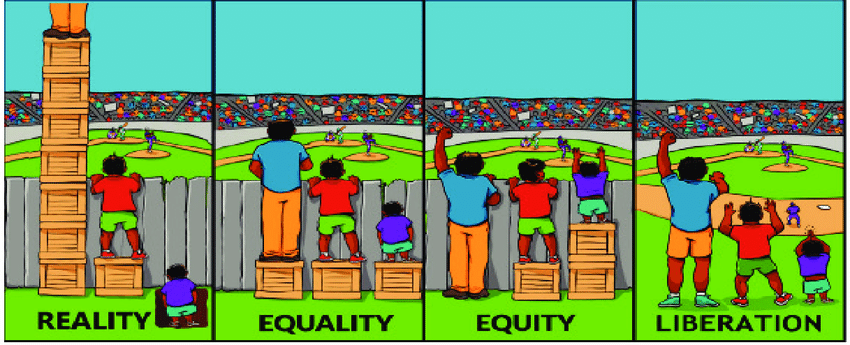

Our jobs are to make reading and learning accessible to the students and staff in our schools. In order to do this, we must understand the barriers to accessibility that exist within our school community and the specific needs of our students. Accessibility is about supporting students with both visible and invisible needs- physical, cognitive, gross motor, fine motor, social-emotional, linguistic. And, as these popular visuals demonstrate, accessibility benefits everyone:

In a 2004 article for Teacher Librarian, Janet Hopkins offers ten suggestions for using assistive tech to make school libraries more accessible. The article is 20+ years old, but the suggestions are just as relevant today. Here’s a brief overview of what I consider her most helpful suggestions:

#1: “Consult with special educators at your school to learn about our students with disabilities and their challenges. Do these students use the library? Why or why not?”

At the beginning of the year, I asked our building's special ed coordinator and our head of guidance about the kinds of physical, intellectual, and social-emotional needs I should anticipate from our population. This year, we welcomed two new students with limited mobility: one who uses a wheelchair and another who uses forearm crutches. I ended up removing some library furniture and changing the layout so these students could navigate the library freely. The head of guidance also told me about a few students in our social-emotional/ trauma recovery program that frequently leave class when dysregulated. I added a coloring mural and a puzzle corner so students could take a few minutes to regulate in the library and made their teachers’ extensions easily visible by the phone.

Talking with guidance and special ed at the beginning of the year was helpful, and I plan to do so every fall. But just because I incorporated the accessibility features above doesn’t mean these students will automatically come to the library. Accessible doesn’t always mean appealing, and in order for students to grow as readers and learners, the library needs to be both.

#2: “Seek out colleagues or members of the school community with assistive technology experience. Find out which resources and services already exist in your district.”

My school district does not have a designated assistive technology specialist. The directors of ed tech and special education share this responsibility and work in close contact with each school’s special ed coordinator. Assistive tech in my district runs the gamut from low-tech pencil grips and adjustable seating options to specialized software programs. Again, some of this tech benefits everyone. For example, when I’m teaching in the library, I wear a small microphone connected via bluetooth to a speaker that sits at the back of the teaching area. This setup was created to help students with hearing loss, but all students and staff benefit from the system because sound gets lost in our library’s lofty ceilings.

Assistive technology and accessibility tools can be visible, like these microphones, or invisible, hidden in the interface of a chromebook or web app. This begs the question, are existing accessibility platforms and resources in my district being used to their fullest extent? Do English teachers know that students can listen to audio versions of course texts through Sora? Do history and science teachers know about the translation features of state databases? Do math teachers know that they can request rulers and protractors with special grips for students who struggle with fine motor skills? Just because the tools are there doesn’t mean people know about them or how to use them.

#3: “Tour your own library to identify barriers to learning…”

My professor introduced our grad class to Project Enable, a 20-hour course designed to raise librarians’ awareness of the needs of students with disabilities and create more accessible library programs, resources, and services. Their Universal Library Design Checklist was an eye-opener. Their 7-part checklist asks questions like:

“Are library services appealing to all users?”

“Does the library provide choice in ways of receiving service and help?”

“Do library services provide effective prompting and feedback during and after use?”

“Does the library design make reach to all components comfortable for any seated or standing user?”

“Do library services provide adequate contrast between essential information and its surroundings?”

While I know my library has strengths and weaknesses, I’d love to go through some of these items with special ed staff, ESL staff, and my student volunteers to get new perspectives. For example, we have a robust world language and hi-low collection, but these books are on the outskirts of the shelves. Can these sections be better integrated into the fiction section to minimize stigmatization? In another example, the library has a user-friendly website, but how can I raise awareness about these resources so that students who prefer, say, online help requests, will want to use them?

#4: “Allocate professional development time for learning about library accessibility and assistive technology.”

Courses like Project Enable and webinars through SLJ are a great place to start. It’s also worth spending time with various tools and apps offered by your district to learn their unique accessibility features. Resources like Sora and state-funded databases have loads of features, too. Sometimes patron requests lead me to discover a new accessibility feature or workaround that I can then share with other staff and students.

AI is a game-changer for accessibility, too. I’ve used AI tools like Diffit and Brisk to differentiate and translate research sources for students when those sources don’t come with the needed accessibility features. AI tools are especially helpful for on-the-spot differentiation so students can engage in the organic research process but still access information at their reading level.

#6: “Become familiar with built-in accessibility features already available on your computer operating system.”

This is an area I’d like to improve on. My students all have chromebooks, and while I’m familiar with several accessibility extensions like Read & Write, I don’t know much about accessibility features baked into the chrome operating system. Let me know in the comments if you have any hacks or favorite tutorials!

#10: “Publicize your accessibility initiatives…”

Advocacy is the name of the game right now. Anything we can do to share our efforts with students, parents, staff, admin, and community members will show how instrumental libraries are to providing a free, appropriate public education (FAPE) for ALL students. Share a photo of your new World Language books! Create a tutorial for using AI to differentiate reading material! Include new tech and grants in your newsletter!

I hope you walk away from this post with new ideas for making your library or classroom more accessible. I hope you have more questions and dive down some rabbit holes! And I hope you find some bit of joy to get you through these last weeks of winter 🧡