Student Volunteers in your Library

When I started as a school librarian, I inherited a wonderful group of student volunteers: the Library Squad. The previous librarian sent me the names of her 7 most trusted volunteers to help with shelving, bulletin boards, and a variety of library projects. These students became my Library Squad leaders, welcoming new students into the group, taking charge on projects, and training volunteers to shelve. Eager to offer volunteer opportunities to more students, I promoted Library Squad during English class orientations and was met with overwhelming interest. I learned a great deal about running a volunteer program from this experience and want to share the highs and lows with you.

Identify tasks that you’re comfortable with students completing versus tasks only you or your staff should complete. Shelving, creating displays, and putting together bulletin boards are great places to start. Does your library have existing programs or routines? Are there ways volunteers can contribute? (Setting up the weekly guessing jar or creating the March Madness bracket, for example). Tasks that have a clear beginning and ending as well as a tangible product are best for building motivation.

Set aside time to train students and anticipate a learning curve. I did not do this well at first. Despite the assistance of my Library Squad leaders, many students did not have a frame of reference for certain tasks like creating displays or bulletin boards. Try the “I do, we do, you do” approach. If your goal is for students to create displays independently, model your process for one display, work together for a second display, then set students free for a third display.

Be realistic but firm about task timelines. Students will take longer to do a task than you’d take by yourself. It takes me maybe 15 minutes to shelve a cart of books, but it can take my students 25-30 depending on who shows up to volunteer. Similarly, if I want students to create a bulletin board for summer reading recommendations by the first week of June, we need to start brainstorming and establish a timeline when we return from April break. Create a calendar of deadlines, and allot more time than you think is necessary for each project.

Run a volunteer orientation, and make training materials readily accessible through printouts, a Google Classroom, a volunteer board, or a combination. After English class library orientations, I gave students a link to a Library Squad interest form. Students who expressed interest in volunteering were invited to volunteer orientation where they learned expectations as well as how to shelve. At the end of volunteer orientation, students could decide whether or not they actually wanted to volunteer. This was the point where I had students join the Google Classroom and give me their availability.

Introduce everyone to everything, but assign jobs based on student strengths. The previous librarian instituted a routine that all students must shelve when they arrive at Library Squad. I kept that routine this year but found that a) some students were better at shelving than others, and b) this routine left less time for students to work on special projects during a volunteer shift, which meant that projects took longer. Next year I will ask for shelving volunteers (usually the students who want to shelve are the best at it!) so that other students can get right to work on projects.

Put a cap on the number of volunteers in the space at one time. This was my biggest lesson learned this year. I hate saying no to people, especially if it means denying them an opportunity, so there were times I had 35 student volunteers in the library at once. It was chaotic to manage. I didn’t get to spend quality time with everyone and wound up inventing tasks to keep students busy. If you want to “hire” a larger pool of volunteers, create a rotation or schedule that makes it clear who should and shouldn’t be in the library on a given day. Additionally, consider the amount of students who visit the library for book checkout during your planned volunteer time. You need to be available to them as well.

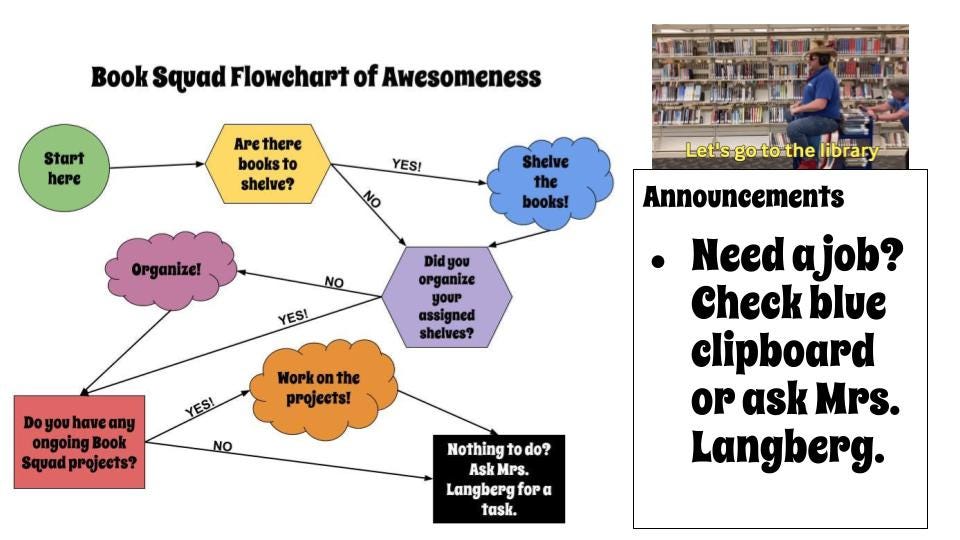

Create systems that encourage student responsibility. For me, this looked like a Google Form for students to track volunteer hours, a flowchart, and a task clipboard. I refused to sign off on hours that were not logged in the Google Form, so this forced students to keep track of their own hours and reach out to me if they needed a signature. I credit my public library boss for the flowchart idea. I projected our Library Squad chart on the board during volunteer time so students knew what they had to do. If they ran out of tasks, they could check the clipboard next to my desk. As tasks arose that I thought students could handle, I wrote them down on the clipboard with specific instructions and the locations of any needed materials. The clipboard and flowchart systems helped students answer their “What should I do now?” questions and freed up my ability to circulate and check in with students.

Develop boundaries around off-task behavior and grades. Going into this experience, I (perhaps naively) assumed that students who volunteered with Library Squad would be eager to work and would be on top of things academically. While this was true most of the time, I had to deal with several older students who spent volunteer time socializing or working on homework. Because I didn’t set consequences for this up front, I seemed much more like “the bad guy” when I asked students to work on something or go back to study hall. Next year I am planning to introduce a 3 strikes policy during volunteer orientation. Additionally, since I have admin access in our student information system, I have the ability to check student grades. I plan to check volunteer grades once per term next year so I can encourage students who are falling behind to take a break from volunteering.

Take and solicit suggestions. Students are your primary audience, and they will always have opinions about what they want and need from the library. Two huge projects the Library Squad completed this year were actually suggested by volunteers: a set of library murals and updating the realistic fiction label covers so they were a more distinct color from our historical fiction label covers (easier shelving and browsing).

Celebrate your volunteers! Thank your students at the end of every volunteer opportunity, and offer specific praise for student creativity and initiative throughout the year. At the end of the year, set up a party to celebrate the tangible contributions your students have made to the library and their school community. This year I hosted two end-of-year parties: one for my large group of volunteers and one for my leaders. At the leader party, I sought their input about what went well and what needed to improve. We also picked Library Squad leaders for next year. At the larger party, I ran through a slideshow of their accomplishments, talked to next year’s leaders, and served snacks.